|

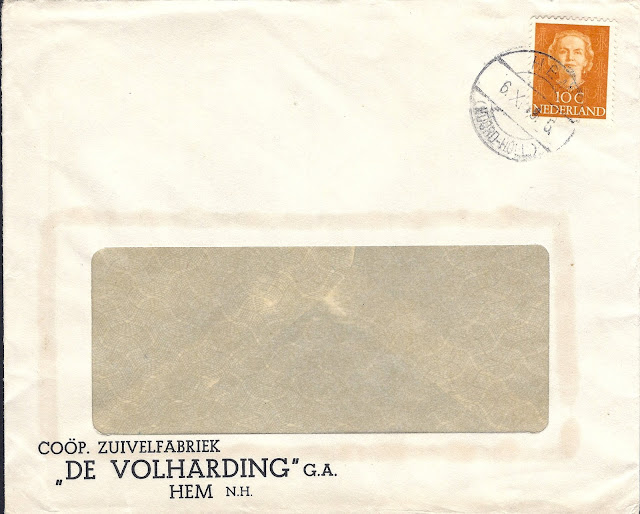

| Dutch parcel card attached to three packages sent to Cetinje in November 1913, then the capital of Montenegro. The parcel card is franked with 3 x 1g, 50c and 25c Wilhelmina Fur collar. This was the correct rate for 3 parcels weighing up to 5 kg. For a single parcel/package weighing 2-5 kg to Montenegro you would have to pay ƒ1.25g between 1904 and 1914. So 3x 1.25 makes the correctly applied postage of 3.75g. |

When Slavo Ramadanović brought the Montenegrin declaration of war to Austria-Hungary in the summer of 1914 he probably realized how reckless this move could be. As General Director of the department of foreign affairs of this small Balkan nation he was in charge of all things foreign, but in most cases his tasks were limited to do business with Montenegro's neighboring countries and his duties didn't have profound impact. A declaration of war surely did shake things up. Although Montenegro had been an independent nation since 1878, its location and modest population size (about 500,000 souls in 1913) made it nevertheless an easy target for large empires such as the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman one. The long Ottoman domination and inhospitable mountains though nurtured stout-hearted folk which was very keen to remain independent. Slavo's declaration of war however put Montegro in a global conflict and grave danger. The outcome of this war (in favour of allied nations) would paradoxically made a messy end to the country's short lived independence.

Christian corner of the Ottoman Empire

For centuries Montenegro balanced on the fringes of the large Ottoman Empire. For centuries too a Prince-Bishop ruled over this Ottoman province, since the bishops of Cetinje defied Ottoman overall rule in the early 16th century and thus the first Metropolitan was elected in 1515. From then onwards this Prince-Bishop continued to rule roughly the shape of Montenegro, albeit paying taxes to the Ottoman sultan in order to remain semi-independent and even more important - christian. Often they had to fight the Sultan's troops, but in most cases the mountains and the mountaineering spirit prevented the Ottomans to sweep the Montenegrins off the face of the earth.

Having said this, I should add that it took almost 400 years for other European nations to formally recognize Montenegro as an independent country. as late as the 19th century the ruling elite in western Europe payed any attention to the Prince-Bishopric, probably due to a languishing Ottoman empire as well to an interest in the so-called 'Balkan spirit'. The clans which defied the Islam for so long were welcomed by British and France romantics who uncovered a proto-European, christian (and at times Homeric) 'race' in these windswept mountains and alongside the rugged Adriatic coast.

So, on the 13th of July 1878 Montenegro finally was granted 'official' recognition from other nations. Prince Nikola ruled over the country since 1860 and continued to secularize the Montenegrin state-apparatus; a process started under the rule of his uncle Danilo who had abolished his title as bishop of Cetinje in 1852. Montenegrin rulers were bishops no more since that year. His nephew Nikola led the now independent nation (about the size of Wales) to a tranquil fin de siècle and grew in esteem amongst other European nobility and monarchy each year. He even payed a visit to the grande dame of Europe herself in 1898 - Queen Victoria. In 1903 there was a political crisis in neighboring Serbia: king Alexander and queen Draga were murdered. Prince Nikola was afraid that a new Serbian monarch would usurp his position as Montenegrin ruler. Luckily his fear remained unfounded. The new king of Serbia, Petar I, was a friend of the Montenegrin court since he had spent some years in exile in Cetinje. In 1905 Montenegro became a constitutional monarchy and to strengthen a democratically elected parliament now

king Nikola organized the first proper elections in the country. This new system appeared to work fine, although it showed a few discrepancies at first.

The future of Montenegro seemed therefore bright if not prosperous at the dawn of the 20th century. A mere 20 years onwards this view was to be considered an utopian one.

|

| Slavo Ramadanović |

Slavo Ramadanović

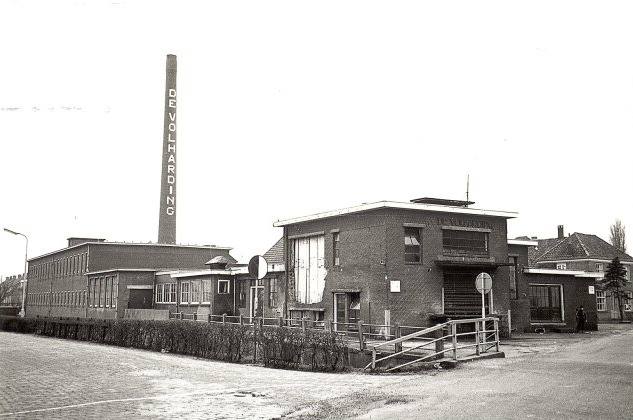

Meanwhile Slavo Ramadanović had maintained several positions in the prince- and kingdom since the early 1900s. According to my own modest digital research I found that he had been consul to the city of Shköder which is situated in what's now modern Albania. The 1st and 2nd Balkan War invigorated king Nikola's idea's of enlarging his realm's size. Already in 1876 he was free to conquer Montenegro's seaboard which was then still part of the Ottoman Empire. In 1913 he was keen to occupy northern Albania and add the rich city of Shköder to his country. With help of Serbia the Ottomans finally surrendered on April 21 1913.

|

| King Nikola observed the surrender of Ottoman troops in April 1913 |

When the 2nd Balkan War was drawn to a close, king Nikola had to transfer the city again into Albanian hands. The Great Powers were rather keen to stabilize the region and prevent a possible longtime resentment between the new nation of Albania and Montenegro. And thus the Montenegrin occupation of Shköder was short-lived.

Ramadanović probably influenced the Shköder (or Scutari) debate and campaign by giving the king advice and information he gained in his years as consul there. He wrote a letter on the 23rd of April 1913 to the Great Powers concerning the occupation and Montenegro's position. He signed the letter with the title of

Le Directeur General so I assume he worked at the department of foreign affairs then already. In another source he is called court marshal Ramadanović, which implies the ties between him and king Nikola were even stronger than I thought. I do not know whether he combined his position as court marshal and director general of foreign affairs or if he was promoted to the department of foreign affairs after having been court marshal to king Nikola. Unfortunately I haven't found any more details on mr Ramadanović yet... Information about him - at least online - seems to be very sparse and most available documents are in Montenegrin or Serbian. Languages I do not even dare to translate.

|

| 3x 1g Wilhelmina Fur collar stamps cancelled with the large round Amsterdam 2 postmark between 7-8 p.m. on the 27th of November 1913. Amsterdam 2 was the sub-post-office at Amstel 212. |

Dutch parcels for the Black Mountain Kingdom

Now we return to the postal history bit of this blog entry. The Dutch parcel card (or for English readers parcel post label) is franked with a lovely combination of 3 Wilhelmina fur collar 1 guilder stamps, alas all detached from each other, but nevertheless a rather handsome trio. To make up the postage of 3.75g the postal clerk added a 25 cent and a 50 cent stamp from the same series as well.

|

| Wax seal of the Bataafsche Hypotheekbank Amsterdam |

The parcel card was addressed to the wife of S. Ramadanović, but what the 3 parcels exactly contained remains a bit of a mystery. We only know that one of them was a packet (

un paquet) and the other two were (small) boxes (

deux boîtes). It took my some time to decipher the craquelé wax seal which could have helped me further trace the contents of the parcels. Unfortunately the sender tuned out to be the

Bataafsche Hypotheekbank in Amsterdam, a mortgage bank located in Amsterdam. Mrs Ramadanović could have owned a so-called covered bond, a very strong bond covered by the mortgages issued by the bank. Still, it remains a bit curious what a Dutch mortgage bank could have possibly sent to a woman (!) in Montenegro at the time. Valuable items? I guess not, since the parcel card doesn't mention any declaration of value and postage for an

avis de récepetion hasn't been applied (10c).

At least S. Ramadanović signed on the reverse of the card that she/he(?) received the parcels. Alas, there is no arrival postmark present, although various transit postmarks are in place: Emmerich (28th of November), Dresden (30th of November) and Vienna (1st of December).

A smart vanishing act

At the beginning of December 1913 the citizens of Montenegro and inhabitants of Cetinje couldn't have predicted that within 3 years Montenegro was on mercy of neighboring Serbia. After a disastrous campaign the Serbian army gave way to Austro-Hungarian troops in January 1916. King Nikola who sided his troops with the Serbians surrendered, fled to France and went into exile there. In July 1917 a declaration was signed on Corfu, which the Serbian army had chosen as their place of exile. The allied nations which were present barely mentioned the existence of Montenegro. They eagerly wanted to have things sorted on the Balkan and therefore were in favour of the Serbian idea to create a 'Yugoslav' union. Moreover, the allied nation rather focused on Albania than on the rest of the Balkan at the end of 1917. On the 29th of October 1918 the Yugoslav project came to life in Zagreb, Croatia. A mock referendum was organised in Montenegro by a newly created 'Grand National Assembly'. The old parliament (which wasn't in favour of joining Serbia or a referendum) was sidetracked in these turbulent times. The outcome of this Serbian led referendum was hardly surprising: Montenegro seemingly wanted to join Serbia in the Yugoslav project. The allied nations mistakenly held the so-called National Assembly at Podgorica as the old legitimate parliament in Cetinje and so the deal seemed settled. A grave mistake retrospectively, but it suited the allied nations well back then: better a strong, unified Yugoslavian state than a fractured Balkan again. On the 24th of November 1918 Nikola was dethroned and the states of Serbia and Montenegro merged - or rather: Montengro was annexed. It took the country almost ninety years in order to regain independence. On the 3rd of June 2006 Montenegro declared itself independent again.

|

| The so-called Podgorica Grand National Assembly in 1918 |

What would Mr Ramadanović have thought about this swift vanishing act? Could Montenegro be seen as victim of the 'Friendly ally syndrome', in order to please Serbia for its sacrifices? It seems likely, although Ramadanović himself couldn't have known that himself. The British envoy who worked in Cetinje between 1911-1916, Sir John De Salis-Soglio, was charged with the Serbian annexation of Montenegro in 1919. He uncovered how Serbia had annexed Montenegro by illegal means and reported his observations back to London. He advised the government not to believe the Podgorica assembly, but listen to the legitimate Cetinje government and king in exile instead. In Westminster they suppressed his report in order not to provoke interference. Only at the end of the 20th century his report was made fully public and the unveiled details do not spare Serbia's intention a bit. The UK deliberately blocked his advice and was therefore compliant with Serbia in Montenegro's vanishing act. So how could you summarize Montenegro's turbulent WWI years ? I've come to the following tricolon: A country overlooked? Partly. A country forgotten? Hardly. A country sacrificed for the sake of others? Undoubtedly.