|

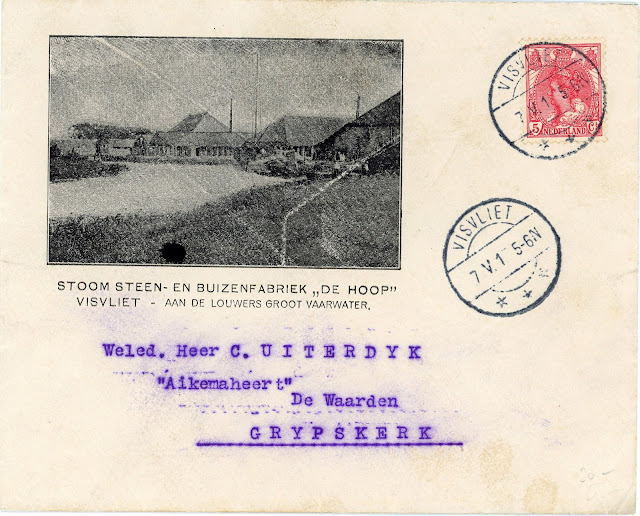

| Signal House at Vlodrop along the Iron Rhine railway near the German border in the 1930s. The area surrounding Vlodrop has been declared a national park in 1990 which resulted in the closure of the railway. |

To this day, needless disputes between nation states stand in the way of closer European cooperation. At a time when Europe should have a democratic response ready to destructive dictatorships and pandemics, stupid trifles such as border disputes ensure that the EU remains ineffective and, more importantly, indecisive when it comes to foreign policy and rapid action. Even closely cooperating states such as Belgium and the Netherlands deal with disputes which date back centuries. One example is the Iron Rhine, a railway which has fallen into disuse since the late 1980s and which once formed an important trade artery between Antwerp and the Ruhr area.

In the treaty of London of 1839, in which the actual division between the Netherlands and Belgium is recorded, both parties agreed that Belgium should reserve the right to establish a direct connection between Antwerp and Prussia through Dutch Limburg. During the ten years that Dutch Limburg fell under Belgian rule, the economy of Belgium had increasingly focused on the strong Prussian economy of the Ruhr area. The stipulation that eastern Limburg would become part of the Netherlands could mean a death blow for the port of Antwerp. A solution was therefore found in a connection in the form of either a new canal to be dug or a railway line to be built. Just as the right of way will continue to generate court cases for landowners, the international variant of it will also cause friction between two states.

|

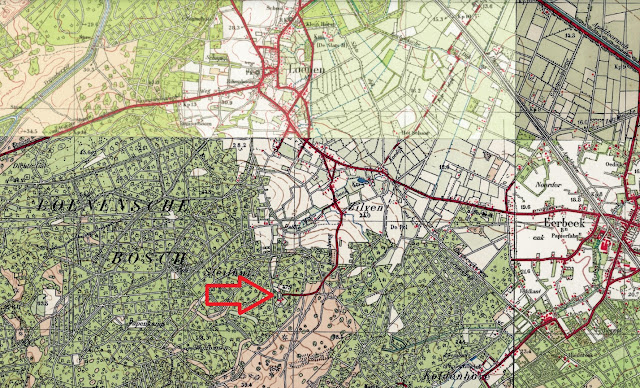

| Route of the Iron Rhine between Antwerp and Mönchengladbach and thereby crossing the Netherlands |

The route of the to be established connection between Antwerp and Prussia already became a point of contention in the 1860s. Belgium saw the benefit of building a railway at the point where Dutch Limburg is narrowest: at Echt. The Netherlands tried to change the route to Northern Limburg. I believe that the interests of the regional economy played a major role in this. Although a railway line had already been built between Maastricht and Venlo in 1865, an East-West connection was still missing in North Limburg. Weert could thus be added to the Dutch rail network by means of a rail project – an this would partly be financed by Belgium. In the end it was decided to build a route from Hamont in Belgium via Budel, Weert and Roermond to Mönchengladbach. Instead of 15 km of track over Dutch territory, the final length of the route was almost 30 km! The Dutch concession was granted in 1873 to the Belgian Compagnie des Chemins de Fer du Nord de la Belgique. This concession would expire after 99 years in 1973. In 1879 the route was ready.

|

| Route of the Iron Rhine in the Netherlands with Roermond right of the centre. |

In terms of postal history the Iron Rhine railway has not overtly been spoiled with postal markings. Nevertheless there existed TPO (travelling post offices) on board trains which ran Roermond/Vlodrop v.v. and Budel/Roermond v.v. which used their own postmarks. Several stations along the route will also have had their own baggage office markers. It should be pointed out though that the share of domestic passengers on the route sections Budel-Weert and Roermond-Vlodrop was small. The Iron Rhine was mainly used for freight transport and international passenger trains.

The border crossing between Belgium and the Netherlands near the town of Hamont is really curious from a postal history point of view. As early as 1810, in the middle of the wild Brabant moorland, there was already a border office where mail travelling to France was marked with the three-line Hollande/Par/Hammont marker. The choice of the Iron Rhine route therefore does not seem entirely coincidental. But why was this medieval town surrounded by peat and bracken a border office in the first place?

|

| Entire letter from Haarlem to Francomont near Vervier in French occupied Belgium (13-2-1810). The Marque d'entrée which reads Hollande/Par/Hammont was applied in Hamont close to Budel. |

Since the Peace of Münster in 1648, the medieval town of Hamont had grown into an international hub for postal traffic. Mail from the Republic found the quickest way to the garrison of Maastricht and cities such as Liège, Aachen and beyond by crossing the border at Hamont. The central exchange point in the Netherlands being Alphen aan de Rijn where mail from several cities was collected before being forwarded to the south. Private initiatives were the basis of postal traffic in those days, but the strong economy of the Republic ensured a steady influx of correspondence. From 1667, postilions even carried out night trips to Maastricht. From about 1750 these private enterprises were gradually transferred to the States (State Post). The ride Alphen-Hamont and beyond was also maintained.

In the Napoleonic period a postal treaty was concluded between the puppet Kingdom of Holland and the French Empire in 1808. Hamont and nearby Achel remained two important customs points en route to France. The Décret Impérial came into effect on 1 August 1809 and would eventually remain in effect until 1 April 1811. This in spite of the incorporation of the Kingdom of Holland into the French Empire in 1810 and the subsequent applicable declaration of all French laws and regulations. For the territory of the former kingdom, therefore, nothing changed until April 1 1811. The 1809 Décret Impérial stipulated that the Kingdom of Holland would be divided into 3 rayons or districts for the sake of a more unified rate calculation. This division surely had some benefits, but rate calculation remained a somewhat cumbersome practice. Four official border crossing points were created. One at Hamont and the Hollande/Par/Hammont border marker was created for outgoing mail. There was no Dutch equivalent for this marker. Incoming mail would incidentally be marked with a red crayon capital M (for Middelburg), B (for Breda) etc. Because the Hollande/Par/Hammont marker was only in use until the expiration of the postal treaty on the 1st of April 1811, strikes are quite rare.

|

| Hamont and surroundings during the time of the reunited Netherlands (1815-1830) |

In contrast to the route of the Iron Rhine, which is oriented east-west, the previous postal route was north-south. A substantial difference. In this light, the two routes have only one common denominator: that both traverse Hamont. In recent years there has been much talk about a possible reactivation of the Iron Rhine with a view to international commuter transport and the active promotion of public transport in the context of climate laws. A first step has already been taken: the electrification of the still existing passenger line Mol-Hamont in Belgium. The Netherlands had stipulated this condition in order to realise the reopening of the Iron Rhine. One of the arguments with which the line was closed in the 1980s was the endangered fauna in the Mijnweg national park near Vlodrop, which was threatened by the diesel fumes of the freight trains.

|

| The disused stretch of railway at Vlodrop in 2007 |

Reopening can only take place if the route is fully electrified. But even now an important condition (the electrification of the Belgium stretch of railway) has been met, the reopening of the relatively short Hamont-Budel-Weert section of track is currently being derailed by the Dutch government. Prorail (the Dutch rail manager) estimates that the cost to reactivate and electrify the stretch would amount to a staggering 50 million euro's - which equals €5000 for every meter of track! The Flemish press now suspects that other interests are at play: if the section up to Weert is reopened, the reopening of the entire Iron Rhine will only be a matter of time. The port of Rotterdam has a lot to lose from this, as do Dutch rail carriers and therefore - to continue this (railway) line of thought - Prorail as well. If (largely) green freight transport becomes faster and easier from the Ruhr area via Hamont to Antwerp, the Dutch state will suffer a loss of income. So the neoliberal spirit that (still) controls The Hague makes up enough arguments not to reopen the Iron Rhine for the time being e.g. the outrageous cost estimate. The result: an old-fashioned, vulgar border dispute which is silently being fight out. The students and commuters living in East Flanders and for whom a direct rail link to Weert and from there to Eindhoven and beyond would be a great win, lose out on this political game.

Let's hope that the old international post route through Hamont may inspire the Dutch state to put aside their nonsense arguments and old objections to solve this unhelpful obstacle for further EU cooperation.

A great Podcast on the recent mud fight over the Iron Rhine railway can be listened to here. Two journalist (Kato Poelmans and Timmie van Diepen) of the Flemish newspaper Het Belang van Limburg discuss the history and uncertain future of the line.

.tiff)